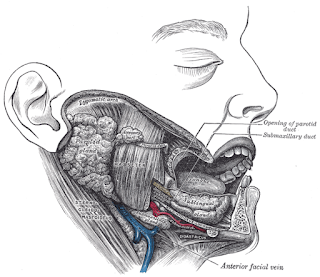

The mandible is your lower jaw bone, as you can see above. There are eight muscles associated with elevating and depressing this jaw bone, so I'm going to start with the elevators.

The first mandibular elevator is the masseter.

This is the big muscle you can see right where the man's cheek should be above. This is the most powerful, and most superficial, of all the mandibular muscles...and if you suffer from TMJ (or TMD), then this muscle is the source of a lot of discomfort for you. This muscle originates from the zygomatic arch (or cheekbone) and inserts into the mandible. You can feel it bulge out near the outside of your cheeks if you clinch your teeth (hence why this muscle gets extremely tight in cases of TMD). This muscle elevates the mandible, bringing the jaw closed.

The temporalis muscle is under (or deep to) the masseter, and it's bloody huge!

|

| Seriously! Look at that thing. |

This muscle happens to be the reason I get tension headaches above my ears during exams. (I tend to clinch my teeth during deep concentration.) It originates from the zygomatic arch (or the "cheekbone") and inserts into the mandible. This is the muscle that elevates and also pulls the jaw back if the jaw bone is protruded forward. It also appears to be capable of more rapid movement than the masseter...but it's not as powerful as it.

The medial pterygoid is not the name of a dinosaur, as much as the word "pterygoid" seems like it (at least I think so). It originates from the medial pterygoid plate and inserts into the mandible. This muscle acts along with the masseter to elevate the mandible.

|

| The arrow is pointing to the medial pterygoid, and the lateral pterygoid can be seen as the top muscle here. |

The final elevator is the lateral pterygoid and comes from the sphenoid and inserts into the upper portion of the mandible (the part that comes right up near your ear.) Contraction of this muscle moves the jaw forward, which is very useful when used along with the other elevators during chewing.

The first depressor we'll go over is the diagastric muscle, which was also mentioned as a laryngeal elevator. This muscle does elevate the larynx via it's connection to the hyoid bone, but it also depresses the mandible if both the anterior and posterior bellies work together.

In fact, a lot of the laryngeal elevators come back into the picture here. The mylohyoid and geniohyoid are also both laryngeal elevators and mandible depressors.

The last mandibular depressor is the platysma, which is a large muscle of the face as well as a mandibular depressor. This muscle originates from the tissue around the clavicle and inserts into the mandible and a few other facial muscles we'll go over next time. It's runs above the sternocleitomastoid.

*Seikel, J. A., King, D. W., & Drumright, D. G. (2010). Anatomy and physiology for speech, language, and hearing. Clifton Park, NY: Delmar.

No comments:

Post a Comment