Prior to this video being taken, I was enjoying thinking of my voice as functional and healthy. Seeing the paresis in action again, however, brought back the emotional memory of the first time I saw it. All the "how can I sing opera without an intact voice?" came flooding back into my head. Thus, I put the video away in a file on my computer and never looked at it past that spring semester in 2014. Until that SLP wanted to see it.

A few caveats: I wasn't tolerating the rigid scope very well (the one that goes in the mouth). I have a pretty hyper gag-reflex and I was certain I would gag the whole time, so the video is choppy and the SLP taking it never quite got a full shot of my vocal folds. I just want to say that the SLP who took this video is an amazing voice therapist and very skilled with the stroboscope. The fact that she never got a good look was entirely due to my hyper-reactivity. I just never managed to calm myself down! (The one at the ENT's office back in 2009 went through my nose.) The second caveat is that I wasn't singing regularly much at all at this point in time and I had a round of reflux that week so my vocal folds are a little swollen, but you can see the paresis still there.

When the other SLP wanted to see the video a few weeks ago, I realized that I had been avoiding it because I'm much happier thinking about my voice as healthy and functional for me. I've been practicing again and taking voice lessons again and my voice felt great! Why would I want to see it still being an issue? Then I realized that avoiding the video is silly. If I want to stick to my own philosophy of a balanced voice being the whole goal of technique, then I should learn to accept my whole voice--flaws and all. It still is functional for me right now. I am still able to express myself musically through my singing, so I should not be afraid of looking at my full voice for what it is at this moment.

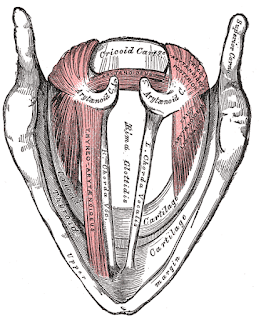

With all that said, here's a little guide to interpreting this video. The front of the throat is at the bottom of the video and the back of the throat is at the top. You can see the epiglottis in full view at the bottom and you can see the root of the tongue where it meets the epiglottis there in most of the video as well. The opening to the esophagus is at the top of the video and is closed whenever you are not swallowing. (The muscle that closes the esophagus functions such that it's tonically closed during it's resting-state.) The right side of the screen is the left side of my larynx and vice versa. The vocal folds are the white strips of tissue you'll see in the middle of the screen--the posterior portion of the vocal folds are first visible around 00:20. There is a bit of redness there as well thanks to the reflux I was dealing with around that time. (I was having an issue getting my PPI prescription renewed with my doctor's office.) The arytenoids are visible near the top of the video. These are the guys you want to keep your eyes on to see the paresis in action. The posterior glottic gap (i.e., the place where my vocal folds don't completely meet during phonation) extends further for me due to the paresis. This is where I "leak air" when I'm singing.

At 0:31: You might need to stop and start the video in short bursts from here, but this is where you can see the left arytenoid doesn't go as far to midline as the right. If you stop and start a few times, you can see the right arytenoid adduct smoothly and quickly. The speed with which the right arytenoid adducts makes it pretty clear the left arytenoid isn't traveling as far. It stops moving before the right arytenoid does.

At 0:48: You can see the left arytenoid "crap out" (very technical term right there). It stayed in an adducted position, or as close as it gets to midline during adduction, so what you can briefly see is my right arytenoid adducting to meet it.

If you think you're seeing any bumps on my vocal folds that look like nodules or polyps, it's actually mucus. This is determined during stroboscopy by the very scientific method of having the patient clear their throat and swallow. If the bump moves off or moves to a different location, it's mucus.

So, those are my vocal folds as they are now (minus the swelling and redness from reflux). Yes, I can still sing with these folds and my voice doesn't fatigue during the day as long as I don't strain when I speak. Essentially, the biggest "enemy" to my being able to sing is tension, since it's still easy to want to "fight" with my voice, particularly on long phrases. But, I think if I stop hiding from my vocal flaws and learn to accept them, I'll start to sing better just by feeling more free to express myself flaws and all!

Edit to add: Also, when I start to glide up the pitch, I start to shift my epilaryngeal area in the manner referred to as "covering" in the pedagogical literature. This is all great and good in the singing world, but it obscures the view of the vocal folds when using rigid stroboscopy. I should have tried for a more "choral sound" during my glide to maintain the laryngeal position. But, gliding is a check for the superior laryngeal nerve (that handles the action of the cricothyroid), and as you can hear, mine is pretty well-intact. Just the recurrent nerve (the one that handles the muscles of adduction and abduction) is a little impaired.