I've had a great comment over on my other blog, Balanced Voice, that I would love to open up to a discussion in the comments. If anyone has the time or inclination to give their two cents, I think it's an interesting topic that needs more exploration in the pedagogical world.

Check it out: Technique vs. expression

Saturday, August 22, 2015

The discussion begins!

Another semester, another workload

I'm getting pretty burnt out of school right now. I'm tired of taking classes, studying for exams, and having homework of any kind (even if it's just reading articles). I suppose this is reasonable for someone in their second year of their PhD program of a new round of degrees after a career change, but I'm just tired. The fall semester is about to begin and I'm dreading the work load that comes with it.

That said, I'm very happy that I decided to continue for the PhD in Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences. I'm really enjoying getting to dig really deep into the research literature, learning how to design scientific studies (there's a lot of planning to do!), and getting to guest-lecture in courses. The mentoring I'm getting from the faculty at my university is really amazing! I'm at one of the top schools for SLP for my PhD. I say that not to brag, but because I want to say learning how to think critically from some of the best researchers in the field is incredibly exciting! It's also cool to see these top researchers day-in and day-out and then to see other people at other schools get all "fan girl" or "fan boy" over these people I get to work with everyday. Maybe this is what it feels like to be a young artist at the Met!

I'm also doing my clinical fellowship on a part-time basis in voice, with some other clients with things like traumatic brain injury and Parkinson disease to round out my hours. In the US, everyone who wants to be an SLP has to do a clinical fellowship after they finish the clinical master's degree. The governing body for SLP, ASHA, dictates a certain number of hours for the CF, so mine should be completed in two years (hopefully) at my current part-time hourly rate. Usually, this clinical fellowship is called the "CFY" for "clinical fellowship year," since it's usually completed after 9 months of full-time clinical work (so that those SLPs who work in the school districts still complete it after their first year of work). But, since mine is part time and will take me a little longer than a year to complete, I'm calling it my "CF"--minus the "year" part.

This semester, I will be completing my PhD minor in neuroscience (which involved taking all the first-year PhD required courses for neuroscience at my university) by taking a biological computer modeling course. For this, I need to brush up on my calculus. This is the course that I'm worried might be a heavy course load. (Last year, I took a cellular and molecular neuroscience course and a systems neuroscience course for my minor. The cellular one was not quite up my alley--good to know, but not the most exciting material for me--but the systems one was fantastic! Exactly what I wanted from my minor! And the cellular course made a good foundation for the systems one, so I'm glad I took both.) I'm also taking a grant writing class where we'll compose a draft for a grant called an F31. This is the research-dissertation (for PhD students) grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the US. It's a very competitive grant, but my department has a very good record of their students being awarded F31s...possibly due to this really good class I'll be taking. I'm excited about this class because I have a cool project to write on and being forced to plan every aspect of your study, including possible limitations to completing your study, from the very beginning is a BIG skill that all good researchers need. And it's daunting at first! But I'll have good guidance from the professor for this course, so that will be great.

And last but not least, I finally found a good voice teacher where I live, so I'm back taking lessons (sporadically at the moment--once a month or so) and practicing regularly on campus. I'm hoping to get up a program for a recital in town just for fun, but I'm not putting any pressure on myself to make that recital happen anytime soon. I'd rather get my coursework mostly done before I schedule something like that. But it really feels good to be singing regularly again!

And I must say I'm loving the "singing as a hobby" compared to professional work right now. There's something satisfying about not worrying about catching a cold or if I had a little reflux the night before. I can just take a break from singing that day. No big deal! --I guess I kinda feel like just a regular person in that way.

Anyway, if I don't blog as regularly during semesters, blame the calculus! jk. But seriously, I'll try to stay on it a little more now.

That said, I'm very happy that I decided to continue for the PhD in Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences. I'm really enjoying getting to dig really deep into the research literature, learning how to design scientific studies (there's a lot of planning to do!), and getting to guest-lecture in courses. The mentoring I'm getting from the faculty at my university is really amazing! I'm at one of the top schools for SLP for my PhD. I say that not to brag, but because I want to say learning how to think critically from some of the best researchers in the field is incredibly exciting! It's also cool to see these top researchers day-in and day-out and then to see other people at other schools get all "fan girl" or "fan boy" over these people I get to work with everyday. Maybe this is what it feels like to be a young artist at the Met!

I'm also doing my clinical fellowship on a part-time basis in voice, with some other clients with things like traumatic brain injury and Parkinson disease to round out my hours. In the US, everyone who wants to be an SLP has to do a clinical fellowship after they finish the clinical master's degree. The governing body for SLP, ASHA, dictates a certain number of hours for the CF, so mine should be completed in two years (hopefully) at my current part-time hourly rate. Usually, this clinical fellowship is called the "CFY" for "clinical fellowship year," since it's usually completed after 9 months of full-time clinical work (so that those SLPs who work in the school districts still complete it after their first year of work). But, since mine is part time and will take me a little longer than a year to complete, I'm calling it my "CF"--minus the "year" part.

This semester, I will be completing my PhD minor in neuroscience (which involved taking all the first-year PhD required courses for neuroscience at my university) by taking a biological computer modeling course. For this, I need to brush up on my calculus. This is the course that I'm worried might be a heavy course load. (Last year, I took a cellular and molecular neuroscience course and a systems neuroscience course for my minor. The cellular one was not quite up my alley--good to know, but not the most exciting material for me--but the systems one was fantastic! Exactly what I wanted from my minor! And the cellular course made a good foundation for the systems one, so I'm glad I took both.) I'm also taking a grant writing class where we'll compose a draft for a grant called an F31. This is the research-dissertation (for PhD students) grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the US. It's a very competitive grant, but my department has a very good record of their students being awarded F31s...possibly due to this really good class I'll be taking. I'm excited about this class because I have a cool project to write on and being forced to plan every aspect of your study, including possible limitations to completing your study, from the very beginning is a BIG skill that all good researchers need. And it's daunting at first! But I'll have good guidance from the professor for this course, so that will be great.

And last but not least, I finally found a good voice teacher where I live, so I'm back taking lessons (sporadically at the moment--once a month or so) and practicing regularly on campus. I'm hoping to get up a program for a recital in town just for fun, but I'm not putting any pressure on myself to make that recital happen anytime soon. I'd rather get my coursework mostly done before I schedule something like that. But it really feels good to be singing regularly again!

And I must say I'm loving the "singing as a hobby" compared to professional work right now. There's something satisfying about not worrying about catching a cold or if I had a little reflux the night before. I can just take a break from singing that day. No big deal! --I guess I kinda feel like just a regular person in that way.

Anyway, if I don't blog as regularly during semesters, blame the calculus! jk. But seriously, I'll try to stay on it a little more now.

Wednesday, June 17, 2015

New blog, new topics

Hello all! Once again, I let this blog lag quite a bit. Sorry for my absence.

I've been wanting to get back into blogging a great deal, but I've been stuck as to which direction to go in. I wanted to share the things I've learned about the most effective ways people learn complex motor tasks, like riding a bike or, well, singing, but I also wanted to open up a place where voice teachers, singers, and voice scientists could comment and discuss the best ways to go about that. So, I recently decided to make a new blog for that purpose. This blog is going to be more narrowly focused than this one, and I'm hoping it will develop into a great place for any pedagogical questions or issues that arise for any of you. I'm also hoping it can be a resource for new teachers to ask experienced teachers for advice if you're dealing with a tricky voice for the first time.

The current plan is to keep this blog going, but to keep the focus of this blog my own personal and academic journey. The new blog will be where I discuss the scientific evidence from physiological and behavioral studies that I think is often missed in pedagogy coursework. As such, I'm starting off this new one as if folks already have some basic, general knowledge of how the voice works physiologically. I hope you'll check out this new blog and feel free to begin the discussion there on any questions or issues you're currently having, either with your own voice/singing training or as a voice teacher, any questions you have about what science can offer vocal pedagogy.

I hope to "see" you there! http://balancedvoice.com

I've been wanting to get back into blogging a great deal, but I've been stuck as to which direction to go in. I wanted to share the things I've learned about the most effective ways people learn complex motor tasks, like riding a bike or, well, singing, but I also wanted to open up a place where voice teachers, singers, and voice scientists could comment and discuss the best ways to go about that. So, I recently decided to make a new blog for that purpose. This blog is going to be more narrowly focused than this one, and I'm hoping it will develop into a great place for any pedagogical questions or issues that arise for any of you. I'm also hoping it can be a resource for new teachers to ask experienced teachers for advice if you're dealing with a tricky voice for the first time.

The current plan is to keep this blog going, but to keep the focus of this blog my own personal and academic journey. The new blog will be where I discuss the scientific evidence from physiological and behavioral studies that I think is often missed in pedagogy coursework. As such, I'm starting off this new one as if folks already have some basic, general knowledge of how the voice works physiologically. I hope you'll check out this new blog and feel free to begin the discussion there on any questions or issues you're currently having, either with your own voice/singing training or as a voice teacher, any questions you have about what science can offer vocal pedagogy.

I hope to "see" you there! http://balancedvoice.com

Saturday, October 18, 2014

You have a vocal injury? How did you do it?

Singing world: We have a serious problem, and it must stop.

This problem is so pervasive that it still exists in the clinical world too: The idea that someone might "cause" their vocal injury, and in doing so, that they (or their private voice teacher) are somehow guilty of some horrendous wrong-doing. (Side-note: This mentally does not exist in any clinician that I would ever recommend to someone. It still exists in some, but not all.) (Okay, side-side-note: I was just a guilty as everyone in this mentality prior to entering speech-language pathology, but I have turned 180 on these beliefs and I think everyone else should too. Here is why.)

Let's start with this example: The Olympic gold-medalist Lindsey Vonn. If you clicked on the link, you'll read about how she wasn't able to complete in the 2014 Winter Olympics due to a knee injury.

How many of you out there thought to yourself: "Well, Lindsey Vonn is a terrible skier. She just doesn't have good technique. She doesn't even train with a good coach. I heard she makes poor decisions in terms of what course to run, what competitions to sign up for, and when to stop. She just doesn't have what it takes to really have a career as a skier."

Personally, I've never heard of anyone looking at a high-level athlete and scoffing at an injury they may sustain. So why do we singers do that to each other? Now replace "Lindsey Vonn" with "Maria Callas," "Natalie Dessay," or "Julie Andrews." Do the above comments seem more justified all of the sudden? If so, WHY? Why are professional singers any different than high-level athletes? Why would sustaining an injury of any kind make a singer (or their voice teacher) automatically deserving of scorn?

Here's the big secret that really shouldn't be a surprise: No one intends to injure their voice! It's an accident that's scary to deal with. There is no reason people dealing with the emotional impact of those consequences should also carry the guilt of causing their injury. It's not a necessarily a sign of poor singing technique and it also isn't necessarily a sign of bad voice teaching. Often, the direct cause of an injury is very hard to determine. (NOTE: Cause is different than time of occurrence. In some injuries, like a vocal hemorrhage, we can determine the time or day that the injury likely occurred. However, the direct cause of the hemorrhage can still involve multiple variables.)

Did you ever:

-Go to an amusement park and lost your voice a little from screaming on the roller coasters?

-Sing a well-paying gig while sick because you had just enough voice to get through the gig?

-Go out to noisy restaurants/bars regularly with your friends/cast mates after singing for hours daily?

-Unknowingly sung (uncomfortably) with acid reflux for several months before getting looked at by your doctor?

I bet most of you have at least done one of the things on that list. In some people, some of these behaviors can contribute to the developing of a voice disorder and in others, no disorder develops. Truth is, even the best vocal scientists can't predict who will develop a voice disorder/injury and who won't. Too many factors are at play.

Blame does nothing but inflict additional damage to someone dealing with a medical condition. Injuries are accidents that happen sometimes to good singers and that need to be dealt with in the best way possible. That is all. Vocal injuries for a singer are exactly like a knee injury for a pro skier. Until we can travel back in time and prevent accidents from happening, guilt and blame does nothing but make it worse. What is needed is a good plan to get the voice to a condition that, ideally, will meet the patient's vocal needs. That is what a medical team (e.g., ENT & SLP) is for.

So perhaps the next time you hear someone say he/she is dealing with an injury, instead of saying "How did you do it?" Say "Oh, I'm so sorry to hear that" and maybe offer condolences and wish them a speedy recovery.

We keep calling ourselves "vocal athletes." It's time we start treating each other as such, especially when an injury occurs.

We keep calling ourselves "vocal athletes." It's time we start treating each other as such, especially when an injury occurs.

Thursday, October 16, 2014

Hitting the ground running…and somehow finishing strong

Well, well. It's been a long time since I've posted, hasn't it? I've been thinking about getting back to blogging so very often over the past two years. I just finished the Master of Science in Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences in May, and I am now in my first semester of my PhD program. My research is focusing on acoustics of voice and speech, and, clinically, I'm getting some fantastic training in order to specialize in voice therapy.

So, when I logged back in and looked at drafts of blogs I left unfinished, I found that wrote a short draft of a post I intended to publish after my first two weeks of grad school. Here it is:

Fast forward two years and I find it's a pretty good description of the program. The pendulum did swing away from the "incompetent" feeling. In a short two years, I ended up becoming a rather competent clinician. But, man, was it an intense and stressful ride to get there!

Of course, now that I'm starting something new again with the PhD program, the pendulum has swung back to "incompetent" again. (Ain't it always the way?) Only this time it's in regards to all the fine details that goes into good research design. I still feel pretty competent as a clinician, though, so that's good.

Anyways, I'm going to do my best to come back to regular blogging. It's been so long that I honestly don't know where to begin. There's some scientific stuff I need to correct in my anatomy and physiology section. I would also like to write up some stuff about teaching singing more efficiently and maintaining a technique. But for now, I might just jump in with things as they are in my life now and fill in as I go. Gotta get my feet wet again with this blogging stuff.

So, when I logged back in and looked at drafts of blogs I left unfinished, I found that wrote a short draft of a post I intended to publish after my first two weeks of grad school. Here it is:

Grad school has started. Folks kept telling me that you'll really hit the ground running in a clinical program, and they really weren't kidding! In the past two weeks I've completed HIPAA training, read 15 articles/textbook chapters, been quizzed on eight of those articles, done my lesson plans for my first two clinical sessions, given those two clinical sessions, read through seven client files, and observed four hours of clinic. My first research project is due in two weeks, and my first exam is the day after labor day.

On the plus side, I know this is all stuff I can handle, and I know that the faculty at my school are approachable, supportive, and brilliant. They totally have our backs. It always feels good to know someone has your back.

So I've been fluctuating between feeling all awesome-sauce and conquistador-like and feeling like a fraud, idiot, and incompetent a**, but I think it's getting better. As long as the pendulum keeps swinging away from the "incompetent a**" feeling and moving more toward the "I've got this" feeling, I'll know I'm heading in the right direction.

Fast forward two years and I find it's a pretty good description of the program. The pendulum did swing away from the "incompetent" feeling. In a short two years, I ended up becoming a rather competent clinician. But, man, was it an intense and stressful ride to get there!

Of course, now that I'm starting something new again with the PhD program, the pendulum has swung back to "incompetent" again. (Ain't it always the way?) Only this time it's in regards to all the fine details that goes into good research design. I still feel pretty competent as a clinician, though, so that's good.

Anyways, I'm going to do my best to come back to regular blogging. It's been so long that I honestly don't know where to begin. There's some scientific stuff I need to correct in my anatomy and physiology section. I would also like to write up some stuff about teaching singing more efficiently and maintaining a technique. But for now, I might just jump in with things as they are in my life now and fill in as I go. Gotta get my feet wet again with this blogging stuff.

Monday, August 13, 2012

Physics of Sound: The Spectrogram (or what the heck am I looking at part 2)

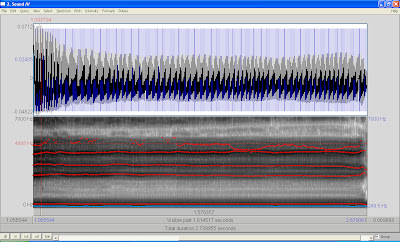

I probably should give a little lesson on how to read a spectrogram, since my next post will feature spectrograms rather heavily. I made all these spectrograms on PRAAT, which is free and downloadable if you wish to play with it. (I know the website looks a little sketch, but I had to get it for my classes using the site I linked to and it's totally safe for your computer.) PRAAT is a lovely piece of software that will record a sound and then give you both a spectrogram and a waveform of that sound. As you look at the images below, the waveform is the image on the top with the thick black band and blue vertical lines, and the spectrogram is the grey-scale mess below that waveform. So, on to the important part of this post!

How to read a spectrogram:

The x-axis (horizontal) is time, the y-axis (vertical) is frequency, and the grey-scale shows amplitude. So a spectrogram can show three dimensions, time, frequency, and amplitude vs. a waveform that shows only two, time and frequency. On fancier programs, the amplitude is sometimes shown in color, like having blue be the softest sounds and red being the loudest, but in PRAAT, the darker the band, the higher the amplitude. In terms of the frequencies, I set the spectrograms to show from 0 Hz to 7000 Hz. PRAAT can display up to 20,000 Hz, but then the formant bands I want to focus on get too squished together. If you click and make the image bigger, you can see a dotted red line with a frequency number off to the left. I set those lines there just to give you some idea of where the upper formant lies in terms of Hz. And remember from the last post that the formant will be somewhere around this frequency, not right at the single frequency itself.

So this is what a typical spectrogram will look like with the upper frequency set at 7000 Hz. (I think PRAAT's default setting is usually 5000 Hz.):

So this is what a typical spectrogram will look like with the upper frequency set at 7000 Hz. (I think PRAAT's default setting is usually 5000 Hz.):

|

|

| Sustained-speech of an /a/ vowel with formants marked. |

|

| Sustained, spoken /i/ vowel, no formants marked in. |

|

| Sustained, spoken /i/ vowel, first five formants marked in red. |

|

| Spoken phrase: "One, two, three, go," no formants marked. |

|

| "One, two, three, go," with formants marked in red. |

Now, some super cool people can actually read spectrograms like they're reading words off the page. I'm not quite that awesome yet, but if you tell me what the phrase is, I can pick out where each specific word is using my knowledge of vowel formants and consonant frequencies. It'd be cool to become that person who can just read them, though!

Now the reason I kept setting the spectrogram to 7000 Hz instead of 5000 is two-fold: First, I wanted to make sure the upper formant wasn't cut off since that formant does occasionally go higher than 5000 Hz, and second, I wanted you to see that there actually is a thick band of amplitude above the 5000 Hz mark, which you can see in the spectrogram above. So there are more "formants" above that 5000 Hz mark...we just don't really regard frequencies higher than 5000 when discussing speech or singing very much. (Although, this article does!) Heck, PRAAT doesn't even mark in any formants above the 5000 Hz area...usually the fifth formant area. But, I wanted to make sure you know that it's not like formants and harmonics just disappear above 5000 Hz. Mathematically speaking, harmonics would just keep on going higher and higher, and so would formants. However, the amplitude lessens the higher you go, so vocal harmonics and formants do dampen out eventually...just not at 5000 Hz.

Up next: The singer's formant! I'mma gonna break apart a common misconception in the hopes that it clarifies what is we're actually doing when we carry over that orchestra.

Physics of Sound Series: Formants, formants, and more formants

According to Raphael et al., the source-filter theory of speech production states that the source of vocal sound, i.e. the vocal folds, is filtered through the air spaces in the vocal tract (p. 330).* This is a fairly simplistic model of vocal production, but it is very useful just because of its simplicity. Other models of speech production out there get a lot more detailed, but for a general, conceptual knowledge of the relationship between the vocal folds and vocal tract in terms of acoustic output, I think the the source-filter model can't really be beat.

So what does this have to do with formants? Well, on the last physics post, I left off by stating that the vocal tract can change it's shape and configuration to filter out different harmonics from the same sound source. The shape of the vocal tract will also amplify certain harmonic frequencies, while dampening others. The resulting "peaks" in amplitude at specific frequency ranges are what we call formants. One important thing to note here is that formants are not the same thing as harmonics. You can think of formants as being a certain specific collection of harmonics, so the first formant is not the same as the first harmonic. The idea of a harmonic is that it is one particular sine wave that is related, mathematically, to the fundamental, but the formants are collections of these sine waves. The language you typically see is that the first formant is around a specific frequency. So while you might read about the singer's formant being somewhere around 3000 Hz, the formant isn't actually only at 3000 Hz, it's just a collection of frequencies centered somewhere around 3000 Hz. I think the semantics might get a little fuzzy there for a lot of people, but what seems like a little, unimportant detail actually makes a big difference when discussing harmonics vs. formants. If you use those terms interchangeably, you'll just confuse the folks who know they're different things and then you'll get confused that they're confused and yadda yadda yadda...

Think of it like this: Let's say you have a collection of all the Star Trek episodes from every Star Trek series, even the crappy ones. If you consider the first series, the original Star Trek, as the fundamental, the first "harmonic" would then be Star Trek: The Next Generation, the second would be Deep Space Nine, the third Voyager, etc. However, it's possible that if these "harmonics" get filtered into formants, the first formant could consist of the first five seasons of The Next Generation, with the last two seasons filtered down to really low amplitude. The second formant could be the last four seasons of Deep Space Nine, with the first three seasons of DS9 being filtered down. The third formant could be the last five seasons of Voyager with the first two seasons filtered down, etc. See the difference? So harmonics are the building blocks of formants, but harmonics come from the resonance of the vocal folds themselves and formants come from the resonance of the acoustic filter or vocal tract.

What's great about formants is that they happen to be the way we distinguish vowels during speech. In fact, the relationship between vocal tract shape and the acoustic output (vocal sound once it exits the mouth) is so interrelated, we are able to classify vowels by both the vocal tract shape and the acoustic output, depending on what we're talking about. I.e.: Talking about articulation? You'll be talking about the shape of the vocal tract made by the articulators (tongue, soft palate, etc.).

If you happened to click over to that Wikipedia article on vowels, you probably noticed there's a section on articulation and a separate section on acoustics. The position of the tongue in the mouth happens to make the biggest difference to the overall shape of the vocal tract, and so, a lot of vowels can be categorized by place of tongue articulation during production. For example: An /i/ ("ee") vowel is categorized as a high, front vowel because the tongue is positioned very high near the roof of the mouth, but it is also positioned quite forward in the mouth and is, therefore, a high-front vowel. A high-back vowel, such as /u/, has the tongue positioned as a "hump" near the back of the mouth, so it's high, but in the back. A low vowel, such as /a/, doesn't involve the tongue in a raised position at all, and is closer to a neutral vowel position, of which the schwa sound is considered the most neutral. (I know a lot of singers consider /a/ as the most neutral vowel, but linguists and speech scientists have researched tongue positions, and schwa is indeed the most neutral. I think the reason singers like the focus on /a/ so much more is that we don't tend to sing schwa very often, and if we do, we don't sustain a sound on schwa. So schwa gets kinda a bad-rap in the singing world, but it is an important little vowel in spoken language.)

Because a larger space will resonant at lower frequencies, and a smaller one at higher frequencies, the formants are a result of the size of the pharyngeal space and/or oral space as determined by the tongue position, primarily. A good example of this is if you tap on a glass with some water in it, then tap again after drinking the water, the second tap will be a lower pitch than the first tap because there is more air inside the glass after the water is gone to resonant the sound. Or a better example: A cello is bigger than a violin. So...there you go. Therefore, in a simplified sense, these tongue positions all correspond to the formant frequencies of each vowel. The /i/ vowel is known for having a low first formant (more pharyngeal space created by the high tongue position) and a high second formant (small oral space created by tongue position,) and in fact, this vowel has the widest space between the first and second formant as it's trademark sound. The /u/ vowel has a low first formant (from the high tongue position creating more pharyngeal space), but also has a low second formant (from the tongue position being near the back of the mouth, creating more space in the oral cavity). Once again, this is a very simplified way of looking at this, but it's an easy way to understand the basic idea. Just be aware that the science of acoustics can get pretty darn complicated in this area.

*Raphel, L. J., Borden, G. J., Harris, K. S. (2007). Speech science primer: Physiology, acoustics, perception of speech (5th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Williams.

So what does this have to do with formants? Well, on the last physics post, I left off by stating that the vocal tract can change it's shape and configuration to filter out different harmonics from the same sound source. The shape of the vocal tract will also amplify certain harmonic frequencies, while dampening others. The resulting "peaks" in amplitude at specific frequency ranges are what we call formants. One important thing to note here is that formants are not the same thing as harmonics. You can think of formants as being a certain specific collection of harmonics, so the first formant is not the same as the first harmonic. The idea of a harmonic is that it is one particular sine wave that is related, mathematically, to the fundamental, but the formants are collections of these sine waves. The language you typically see is that the first formant is around a specific frequency. So while you might read about the singer's formant being somewhere around 3000 Hz, the formant isn't actually only at 3000 Hz, it's just a collection of frequencies centered somewhere around 3000 Hz. I think the semantics might get a little fuzzy there for a lot of people, but what seems like a little, unimportant detail actually makes a big difference when discussing harmonics vs. formants. If you use those terms interchangeably, you'll just confuse the folks who know they're different things and then you'll get confused that they're confused and yadda yadda yadda...

Think of it like this: Let's say you have a collection of all the Star Trek episodes from every Star Trek series, even the crappy ones. If you consider the first series, the original Star Trek, as the fundamental, the first "harmonic" would then be Star Trek: The Next Generation, the second would be Deep Space Nine, the third Voyager, etc. However, it's possible that if these "harmonics" get filtered into formants, the first formant could consist of the first five seasons of The Next Generation, with the last two seasons filtered down to really low amplitude. The second formant could be the last four seasons of Deep Space Nine, with the first three seasons of DS9 being filtered down. The third formant could be the last five seasons of Voyager with the first two seasons filtered down, etc. See the difference? So harmonics are the building blocks of formants, but harmonics come from the resonance of the vocal folds themselves and formants come from the resonance of the acoustic filter or vocal tract.

What's great about formants is that they happen to be the way we distinguish vowels during speech. In fact, the relationship between vocal tract shape and the acoustic output (vocal sound once it exits the mouth) is so interrelated, we are able to classify vowels by both the vocal tract shape and the acoustic output, depending on what we're talking about. I.e.: Talking about articulation? You'll be talking about the shape of the vocal tract made by the articulators (tongue, soft palate, etc.).

If you happened to click over to that Wikipedia article on vowels, you probably noticed there's a section on articulation and a separate section on acoustics. The position of the tongue in the mouth happens to make the biggest difference to the overall shape of the vocal tract, and so, a lot of vowels can be categorized by place of tongue articulation during production. For example: An /i/ ("ee") vowel is categorized as a high, front vowel because the tongue is positioned very high near the roof of the mouth, but it is also positioned quite forward in the mouth and is, therefore, a high-front vowel. A high-back vowel, such as /u/, has the tongue positioned as a "hump" near the back of the mouth, so it's high, but in the back. A low vowel, such as /a/, doesn't involve the tongue in a raised position at all, and is closer to a neutral vowel position, of which the schwa sound is considered the most neutral. (I know a lot of singers consider /a/ as the most neutral vowel, but linguists and speech scientists have researched tongue positions, and schwa is indeed the most neutral. I think the reason singers like the focus on /a/ so much more is that we don't tend to sing schwa very often, and if we do, we don't sustain a sound on schwa. So schwa gets kinda a bad-rap in the singing world, but it is an important little vowel in spoken language.)

Because a larger space will resonant at lower frequencies, and a smaller one at higher frequencies, the formants are a result of the size of the pharyngeal space and/or oral space as determined by the tongue position, primarily. A good example of this is if you tap on a glass with some water in it, then tap again after drinking the water, the second tap will be a lower pitch than the first tap because there is more air inside the glass after the water is gone to resonant the sound. Or a better example: A cello is bigger than a violin. So...there you go. Therefore, in a simplified sense, these tongue positions all correspond to the formant frequencies of each vowel. The /i/ vowel is known for having a low first formant (more pharyngeal space created by the high tongue position) and a high second formant (small oral space created by tongue position,) and in fact, this vowel has the widest space between the first and second formant as it's trademark sound. The /u/ vowel has a low first formant (from the high tongue position creating more pharyngeal space), but also has a low second formant (from the tongue position being near the back of the mouth, creating more space in the oral cavity). Once again, this is a very simplified way of looking at this, but it's an easy way to understand the basic idea. Just be aware that the science of acoustics can get pretty darn complicated in this area.

*Raphel, L. J., Borden, G. J., Harris, K. S. (2007). Speech science primer: Physiology, acoustics, perception of speech (5th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Williams.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)